The Spiciest Directors of All Time

88 of the most distinct filmmaking styles to watch and learn from.

Just like musical artists, a director will often be your first indicator of what to expect from a film. Sometimes you get a curveball, an experimental album or maybe the director’s accountant went to prison and they needed a paycheck. But it’s still the best way to discover quality cinema.

This contemporary Hall of Spice is for budding cinema lovers looking to understand the different cinematic languages used by our distinct storytellers. As there are hundreds of directors to choose from, I will only be promoting exciting filmmakers that I feel are the most unique and pioneering in their styles. I’m providing summaries from a filmmaker’s point of view, but I may update this list over time once my mind changes or if you can convince me with an angry enough comment. If you want to learn more about each one, I’ve left links to some of their greatest films through Filmspice links. Enjoy and let the spice flow!

Abbas Kiarostami

The Teacher. Kiraostami is an Iranian filmmaker considered a master by other master filmmakers including Scorsese and Kurosawa. This is pretty high praise, or is it flattery? Kiarostami is the real deal. Despite working with noticeably limited budgets, he is able to craft realistic and grounded stories in his homeland through Where Is the Friend's House? (1987), capturing life and the essence of Iranian culture. His cinematography is often subtle but can be impressive when he utilizes the beautiful landscapes of Iran. He’s known for longer lenses and objective framing, foremost focusing on his characters in Taste of Cherry (1997). His one of a kind film Close-Up (1990) utilizes a real trial, blurring the lines between reality and art. Iranian filmmakers don’t have massive Hollywood budgets behind them, so they often have to rely on creativity or strong political scripts to overcome limitations.

Akira Kurosawa

The GOAT of Japanese cinema. Kurosawa is known for long to medium lenses, often removing the walls of Japanese interiors to fit the camera as he did in Ran (1985). He is generally recognized for his samurai epics like Seven Samurai (1954), but to be a GOAT one needs versatility. Kurosawa demonstrates his broad understanding of the cinematic language with police thriller High and Low (1963) and political drama Ikiru (1952). He has a classical style of cinematography, often utilizing objective framing and classical camera movement reminiscent of 50s noir. I wouldn’t say he had a vendetta, but considering he was just as good if not better than his Hollywood counterparts, his films seemingly competed and tried to one up them. And he often did.

Alejandro G. (González) Iñárritu

The Human Condition. The Mexican filmmaker is mostly recognized for his interlinking stories style, telling one story through several loosely connected ones in Amores Perros (2000) and Babel (2006). After recognized by Hollywood, he began to experiment through the 2010s. With newfound large budgets behind him, he would go on to utilize novel cinematography techniques like ultra wides in The Revenant (2015) and stitching long shots to appear as one continuous one in Birdman (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014). He can definitely be considered an auteur alongside Alfonso Cuarón.

Alfonso Cuarón

The Searcher. Cuarón is quite similar to Iñárritu in that both are Mexican filmmakers with art house sensibilities. Both implement dogs themes, something very common in Mexican and Brazilian cinema. If they don’t bounce ideas off of each other, they certainly compete or at least look to each other’s works, especially since they both utilize the ultra wide handheld cinematographer Chivo (Emmanuel Lubezki). Cuarón is perhaps a little more standard in his storytelling with less gimmicks, employing straight up storytelling in Y Tu Mamá También (2001). Even his blockbusters have an intimate quality and closeness to them in Gravity (2013) and Children of Men (2006). He is definitely keenly aware of how the cinematographic process is integrated with storytelling, having made one of the most beautiful films Roma (2018) DP’ed by himself.

Alfred Hitchcock

The Godfather of All Thrillers. One of the greatest filmmakers of his time, Hitchcock can also be considered the Master of Suspense. He is often known for quotes such as “There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it” something that greatly applies to his horror films. He is known for leading the way for the first real slashers with Psycho (1960), something considered too violent for its time. The twist was so shocking, he had to prevent late admission to theaters, revolutionizing the film industry. His biggest struggles were often fighting with censorship, often not able to write the stories he wanted, which detracted from his final act in Strangers on a Train (1951). Known for his suspense and psychology, he would go on to influence Shyamalan and many after him that see movies as amusement rides. His greatest film is Vertigo (1958), but I think his best film is Rear Window (1954).

Andrei Tarkovsky

The Philosopher and the greatest Russian filmmaker of all time, Tarkovsky is a master filmmaker known for his philosophical themes. His films seem to be motivated to prove how shallow Hollywood films are. A fraction of the budget and effects, Solaris (1972) was a direct response to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It’s a little understandable why Tarkovsky disdains the technical aspect of filmmaking as one of his masterpieces Stalker (1979) had to be reshot. He instead relies on fundamental filmmaking techniques like framing and blocking, something apparent in Andrei Rublev (1966). Stylistically Tarkovsky employs long droning takes to the effect of becoming hypnotic and trance-like, panning and tracking shots for seemingly minutes on end. Combined with deep focus, he allows audiences to observe and immerse themselves in the surroundings. He is clearly inspired by the vast amount of great writers in Russian literature like Tolstoy and brings the same deep philosophical questions to the silver screen.

Ang Lee

The Hidden. Ang Lee is a Taiwanese filmmaker known for one of the greatest Chinese films of all time, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). Although Lust, Caution (2007) can be considered metaphorical, most of his films like Life of Pi (2012) have broader commercial appeal. He seems very split between western and Chinese culture and understands both very well, even creating a staple in western cinema Brokeback Mountain (2005). He shows no signs of attempting to assimilate with contemporary cinema and sticks to his roots, exploring repressed emotions with a lighter and less psychological tone.

Ari Aster

The Contemporary. The American filmmaker is synonymous with A24, creating hit after contemporary hit. Although he is know for his horrors Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), the filmmaker is also capable of delivering smart political commentary with films like Eddington (2025). The New Yorker has a logical approach to his filmmaking style and openly shares his ideas with specific acuity during interviews. Although he has elevated horror, Aster has much more to do in the political genre. His intellect is apparent in his storytelling, but his execution can sometimes be on the literal side compared to many art house styles.

Bernardo Bertolucci

The Sensation. The most erotic filmmaker of all time? The Italian director is known for implementing seductive sensibilities from Italian cinema, never shying away from explicit content. He normalizes nudity and not in a forced way. The manner he presents it even in the biographical epic The Last Emperor (1987) was completely natural and fitting. Although some of his films may be more scandalous like The Dreamers (2003), Italian cinema actually has even more sexualized styles bordering on soft porn. He is considered one of the greatest filmmakers known for The Conformist (1970), and always delivers a colorful and playful tone to his sensual films.

Billy Wilder

The Martini. One of the greatest American filmmakers in the 50s, Wilder knows how to craft a story whether it is his noir thriller Sunset Boulevard (1950) or comedy Some Like it Hot (1959). He has a great sense of humor and always manages to introduce snappy wit and a light step in his films no matter how cynical they are. His films resemble the sharp, tuxedo wearing gentlemen at parties, clean and intricate pictures we associate with prestigious classics like The Apartment (1960). Ornate dialogue and noir lighting are poetically exaggerated to what we now associate with elite socialites.

Bong Joon Ho

The Korean Oscar. Bong is a Korean director who started making buzz with Korea’s Zodiac equivalent, Memories of Murder (2003). He would go on to become obsessed with films critiquing capitalism first with Snowpiercer (2013) then with his critically acclaimed masterpiece Parasite (2019). At his best he is capable of precise compositions with symbolic framing, propelled by rhythmic editing. Winning best picture motivated him to continue beating this dead horse with Mickey 17 (2025), with his films becoming less nuanced, broader appeal and prestige obsessed. Nowadays he pursues commercial box office success, contradictory to his original vision. Even anti-capitalists need to pay the bills.

Brian De Palma

The Technique. The American filmmaker is known for leading psychological thrillers in the 70s through films like Carrie (1976) and Scarface (1983). His cinematic language is a mix between dark cinema and popcorn thrills. This may be because he seems to borrow indirectly from many of the greats specifically Hitchcock. Though he is able to pilot films in many genres, his darker and campy tone will seem very familiar to modern thrillers, clearly leaving their mark on crime films of the 90s. He borrows long tracking shots from classic cinema while incorporating fresh split screen POV shots and an assortment of fresh filmmaking techniques seen in Blow Out (1981).

Chloé Zhao

The Whisper. Zhao is a Chinese filmmaker that bears no resemblance to Chinese culture. Her films seem to abandon any indication of her heritage evidenced by choosing an acute accented é on her first name. These films include American neo westerns The Rider (2017) and a very impressionable Nomadland (2020). She often creates mood pieces about self exploration and discovery while adding a gentle touch of sensitivity to the tones of her films. Although she is known for indie films, she did direct the superhero slop that is Eternals (2021). Zhao attempts to elevate feminine power in cinema and is a strong voice for female directors.

Christopher Nolan

Temporal Pincer. Nolan is a British filmmaker known for his cerebral and non-linear storytelling. One of his earliest independent films Memento (2000) implemented one of the greatest non-linear storytelling structures ever seen to this day. His next film Insomnia (2002) would be his attempt on how to make a commercially successful hit. After creating The Dark Knight (2008) and finishing the trilogy for Warner Bros., Nolan would have the green light to create any project he wanted in the future. This includes sci-fi masterpieces Inception (2010) and Interstellar (2014). Influenced by Steven Spielberg and Michael Mann’s work, Nolan attempts to bridge high concepts into mainstream blockbusters. As a result, his films are vastly entertaining focusing on visceral real practical effects. He uses star-studded casts to introduce smart concepts, often revolving around time. But sometimes the film’s spectacle takes the spotlight with the emotional drama diluted beneath his fast paced scripts. Nowadays, he seems to attempt at diversifying into other genres with the same vigor.

Clint Eastwood

The Man With No Name. The scowling face of westerns, Clint Eastwood would go on to direct dramatic films, showing he is capable of more than just being a cool cowboy. In the films he directs and stars in, he doesn’t demonstrate that much range, often playing a grumpy, cynical man in Million Dollar Baby (2004) and Gran Torino (2008). However he has shown to play to his softer side in the romance The Bridges of Madison County (1995). Eastwood can be credited with successful hits like Mystic River (2003), but ultimately his films only have surface level depth. Just like the western genre, it’s not particularly serious and his films often lack a logical universe despite being presented with realism. Eastwood’s glory days with westerns like The Good, The Bad And The Ugly (1966) should always over-shadow his directorial work, which can be boiled down to dramatic popcorn flicks.

Coen Brothers

Shakespearean Irony. Joel and Ethan Coen are one of the few director pairs that still work together. While others often split, the two have remained together on many hilarious projects including Fargo (1996) and A Serious Man (2009). They have a unique sense of humor, which can be boiled down to high intellect irony attracting great talent such as Roger Deakins. Despite the legendary DP, their films often look visually subdued and naturalistic especially because they often seem enamored with westerns like True Grit (2010). However, they are known from time to time to create surreal and fantastical sequences in The Big Lebowski (1998). Although they are known for comedies, they are capable of serious masterpieces with No Country For Old Men (2007).

Coralie Fargeat

The Hot Mess. The French director is a young up and coming filmmaker to look out for, known for reviving body horrors with Revenge (2017) and The Substance (2024). A less unhinged version of Julia Ducournau, part of her viral appeal is how she emphasizes shock value in her grotesque experiences with contemporary commentary. Although her themes aren’t as well fleshed out, she only has time on her hands to master her execution. But her visuals are so graphic and extreme that she is bound to reach her destination someday, if not by brute force.

Damien Chazelle

The Band Kid. Chazelle is an American filmmaker, who embodies the dreamer moving to Hollywood. He always directs with the charm of a naive band kid with his masterpiece Whiplash (2014) and was basically given a free check to create whatever he wanted. Music is core to his vision and he would continue to make music related films La La Land (2016) and Babylon (2022). He often has a chaotic nature to his storytelling using whip pans and abrupt cuts. By contrast, First Man (2018) had no music at all. When he’s not directing, he’ll be writing for other films such as 10 Cloverfield Lane (2016). Even in his million dollar blockbusters, his films are always seen through the lens of the aspirational big-eyed dreamer.

Daniels

Wacky Home Movies. Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert are a collective filmmaking duo known for their radical editing. They started pioneering innovative videos in the early days of YouTube with Pockets (2012) before bringing the same cheesy home special effects to independent short films like Swiss Army Man (2016). Their big break was Oscar winning multiverse phenomenon Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), proving that you don’t need massive studios to create fantastic looking effects. Their weird and wacky descent into Wonderland is enabled by inventive and disruptive budget VFX that have yet to shake up the industry. Whether they can be considered true visionaries, only time will tell. Joke or genius, their editing style has intentionally amateur execution and the two never take themselves seriously. Though they in no way resemble traditionally good cinema, they are in some sense the spiciest directors on this list. Or maybe it’s just their hot dog fingers.

Danny Boyle

The Page Turner. Boyle can be considered a British visionary alongside Alex Garland, both of whom worked on 28 Days Later (2002). What makes him unique is he always finds real stories to tell, whether it is an Indian boy in Slumdog Millionaire (2008), a stuck rock climber in 127 Hours (2010), a drug addict in Trainspotting (1996), or the one and only Steve Jobs (2015). Boyle uses fast paced storytelling with unpredictable turns to create a compelling tempo for his edge of your seat dramas.

Darren Aronofsky

The Iceberg. The American director is known for his surreal and disturbing films, most notably Requiem for a Dream (2000). With a name like Aronofsky, there is no doubt he has the capacity to implement layers of dark psychology to his films such as Black Swan (2010). There is an indie realism to his films as seen in The Wrestler (2008), which carries over into his thematic art house films Mother! (2017). To accomplish his darker effects, he will often use practical distortions to create hallucinogenic episodes through lensing, mirrors and visual tricks. Although he is technically an auteur, his budget approach stylistically feels minimal, seemingly an independent acolyte of Kubrick.

David Fincher

The Perfectionist. Starting out as a focus puller, David Fincher is likely the most meticulous director to ever do it, notorious for torturing his cast with dozens of takes. He favors Red Digital cameras, which have the resolution to allow him to crop and perfectly frame his shots with precision. He’s infamous for micro-managing and is considered a master especially after creating subversive thrillers Se7en (1995), Fight Club (1999), The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (2011) and Gone Girl (2014). With his trusty and equally masochistic DP, he commands the screen with impossible camera movements to create omniscient perspectives in his framing. The result is a precisely choreographed and well oiled machine, orchestrated to permit you to see only what he wants you to see. Fincher is outspoken and believes audiences to be perverse. He occasionally takes vacations into other dramas like Mank (2020), The Social Network (2010), and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008), but his calling is making slick modern thrillers, and he’s likely one of the best to ever do it.

David Lean

The Epic. David Lean is known for his adventure epics Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). The English filmmaker is about scale and exotic vistas. His films have a crest of prestige stamped around them for his presentation, characterized by objective blocking and dialogue motivated cinematography. Lean prefers formal dialogue and a classical approach when framing his historical and literary adaptations.

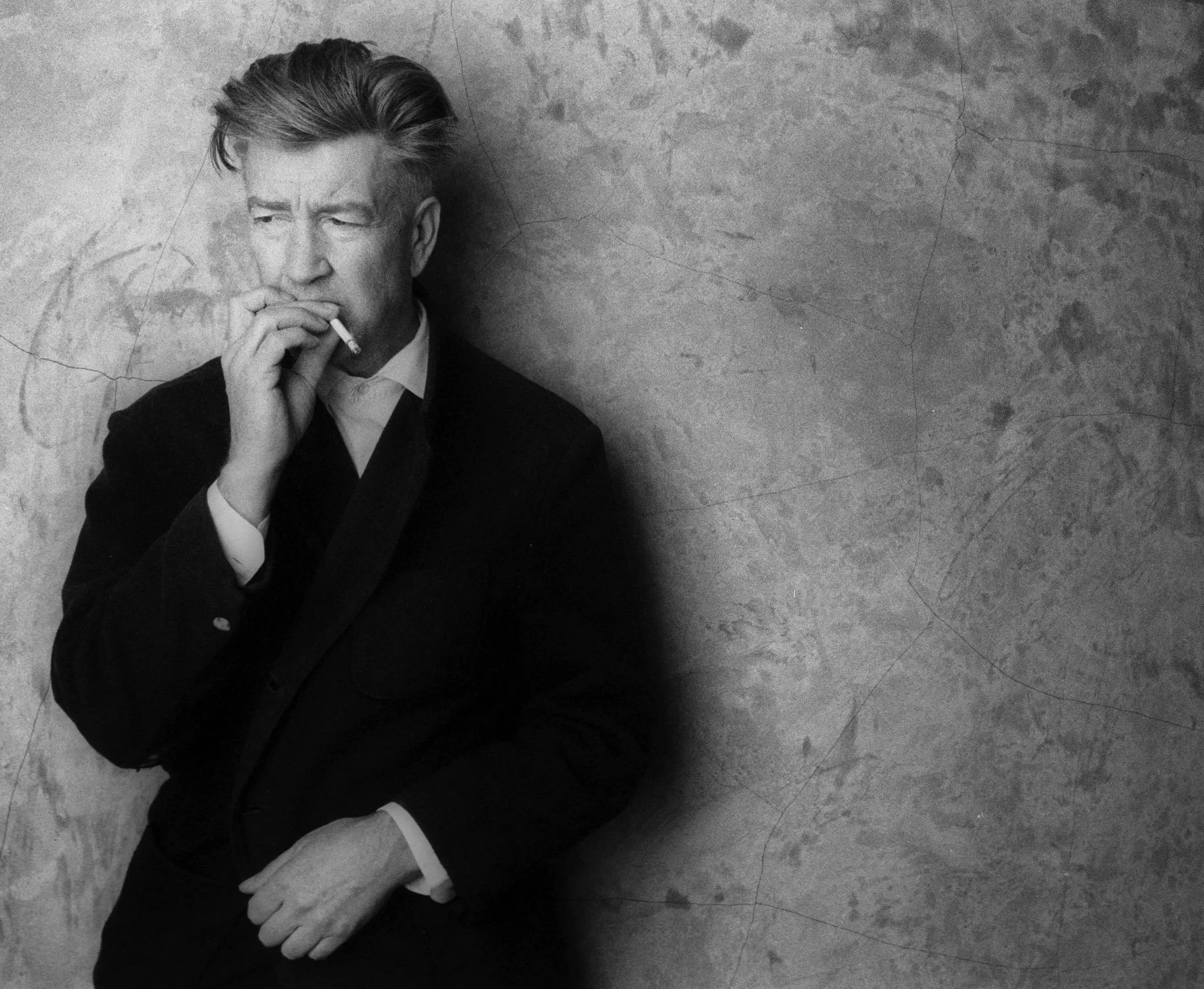

David Lynch

Uncanny Valley. David Lynch is an American filmmaker known for his masterpiece Mulholland Drive (2001). His distinctive style of uncanny surrealism contrasts with the American suburbs as seen in Blue Velvet (1986). There is a sense of perversion and peeping tom voyeurism evoked in his work, juxtaposing normal life with the unexpected supernatural. His films leave a lasting impression in the mind and one can say his films have subconscious impact. Although I personally do not like his television oriented style at all, I think Eraserhead (1977) was genuinely creepy. Nevertheless, his punk freakiness vibe is profoundly influential on other directors including Nolan.

Denis Villeneuve

The Ambiguous. The Canadian filmmaker is in my opinion the most cinematic working modern director and our generation’s Spielberg. Villeneuve is heavily inspired by ambiguous French cinema and is at his foundation an auteur demonstrated by Enemy (2013) and Incendies (2010). He’s clearly influenced by Michael Haneke but has a more mainstream approach, incorporating ambiguous thematic elements into his favorite genre of science fiction through Arrival (2016), Blade Runner 2049 (2017) and Dune: Part Two (2024). What blurs the line between his interpretation of sci-fi and reality is how logically he approaches the details in every universe. However, I think his best works are when his stories revolve around gripping realism seen in Sicario (2015) and Prisoners (2013). What Villeneuve is known for is a deep understanding of the big picture, immersive clarity, all of which execute on his climatic scenes with unbearable tension. He is one of the few that prioritizes the marriage of the soundtrack with image making in order to manufacture truly cinematic events.

Edward Yang

The Criterion Soap Opera. Yang is one of the more well known Taiwanese filmmakers in the west for his epic coming of age dramas Yi Yi (2000) and A Brighter Summer Day (1991). He will often use objective framing, filming the scene at a distance. In my opinion, he is the face of Taiwanese cinema, though I think Tsai creates more cinematic films. Yang is more about archiving real moments and long overarching timelines, which can feel like really long soap operas.

Francis Ford Coppola

The Rebel. Coppola is one of the most influential directors often cited for creating the greatest films of all time The Godfather Part II (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979). He seems fascinated with complex characters and moral ambiguity, taking the risks that are now deemed as the modern standard. The man loves to experiment through sound, technique and storytelling, which really cost him in Megalopolis (2024), a final flop that brought him financially to his knees. So much so that he had to sell his million dollar watch collection. He can be considered rebellious, which is what fuels his drive for innovation in cinema.

Federico Fellini

The Cartoonist. Fellini is an Italian filmmaker with a distinct dreamlike style with swirling camera movement in his visual masterpiece 8½ (1963). As he was initially a cartoonist, his films also have a carnival spectacle to them in La Dolce Vita (1960) and would continue to be grow to be bigger than life journeys evoking a sense of melancholy and joy, critiquing the modern hollowness of life. A pioneer for Italian filmmaking paving the way for others.

Fritz Lang

The OG. The Austrian filmmaker is known for German Expressionism creating the iconic dystopian steampunk universe of Metropolis (1927). He would also go on to create one of the greatest films of all time, M (1931), both of which are landmarks in cinema. Being one of the earliest filmmakers, Lang set the bar by introducing subjective filmmaking, peering through holes and experimenting with unorthodox camera angles. The filmmaker that influenced the master of masters, he would evidently go on to inspire Stanley Kubrick.

George Roy Hill

The Polaroid. Hill is an American director with a gift for storytelling and a powerful sense of narrative. He manages to bring the best screenplays to life whether through The Sting (1973) or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). His films are story and dialogue focused, using vintage and French inspired methods through the use of jump cuts, freeze frames and montages. He blended genres with comical capers while having a bittersweet tone to them.

Godfrey Reggio

The Video Essay. Known for Koyaanisqatsi (1982) with Ron Fricke, Reggio is known for combining cinema with documentary, creating art pieces with no dialogue. It’s quite the impressive feat and though he only made a few significant films, the ones he did make are profoundly legendary. Without a single line of dialogue, his films can carry immense social commentary just by observing daily life, lifting the curtains on the engine behind human civilization. He is a pioneer of time lapse and tilt shift lenses to capture architecture.

Guillermo Del Toro

Gothic Grotesque. The Mexican filmmaker is known for his gothic and grotesque fairy tales, most notably Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Adjacent to Tim Burton, his style is more mystical and diverse, ranging from superheroes in Hellboy (2004) to family movies like Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022). There is a sense of playfulness in all his films but no matter how dark they are he will incorporate secondary thematic elements like steam punk or art deco to lighten the tone in The Shape of Water (2017). This makes his style more visual focused masking his sensitive voice.

Guy Ritchie

Oi, Innit? Guy Ritchie is an English director that you would want to go and get drinks with after a long day of work. Politically incorrect, he is known for his abrasive and course dialogue that can be heard in his gangster comedies Snatch (2000) and The Gentlemen (2019). His playful presentation is attributed to stylish editing and modern transition effects. Flamboyant, unapologetic and guilty pleasures, Ritchie creates fun popcorn flicks that appeal to men and those that enjoy boisterous capers.

Hayao Miyazaki

Box of Dreams. The greatest Japanese animator of all time, Miyazaki films are known for their transcendent anime films. Although the beautiful style seems appealing for children, the stories and themes are clearly for adults, recapturing the beauty of childhood through My Neighbor Totoro (1988). The visuals of his films have surreal and imaginative fantasy, exaggerated in his films The Wind Rises (2013) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). However his masterpiece fantasies culminate with Spirited Away (2001) and Princess Mononoke (1997), two of the greatest films of all time. There will be no one like Miyazaki after he retires and Studio Ghibli cannot replace him. He is principled and notoriously pessimistic especially toward war, even protesting his own Oscar due to the Iraq war. The man is a genius and brings magic lost from adulthood back to life.

Hirokazu Koreeda

The Honest. Koreeda is a modern director from Japan. While Japanese cinema is overshadowed by anime and never reached the same level since Kurosawa, Koreeda seems to be the only thing keeping Japanese cinema hanging on by a thread of relevance. His films are realistic and follow real stories of self-discovery and hardships through Shoplifters (2018) and Monster (2023). Although he is not master level, he is definitely a director to keep an eye on for his organic storytelling.

Hou Hsiao-Hsien

The Memoir. Honestly this guy’s name is impossible to remember, every time all I can think of is a beer or sauce. Hou is a leading figure in the Taiwanese New Wave, which is more of a splash compared to the French New Wave. His films detail the realities and struggles that poor, urban and countryside Taiwanese feel in his autobiography The Time to Live and the Time to Die (1985) and his exotically sensual Millennium Mambo (2001). His films are nostalgic and sentimental, though frankly so personal to him that they don’t really feel they were meant to be watched by mass audiences. His films are slow like taking one’s time in the park, utilizing long cuts panning the camera at glacial speeds in an observatory way. This isn’t about the glitz and glamor, he just wants to document real life.

Ingmar Bergman

The Psyche. Bergman is often compared to Tarkovsky, whom denounces any similarities. Bergman poses existential questions in his films regarding religion in The Seventh Seal (1957) and the subconscious. His masterpiece art house film Persona (1966) is considered one of the first and greatest metaphorical films that has an enduring legacy on auteur filmmaking. His cinematography is artistic in its resemblance to stark monochrome photography while implementing contrast ratio that should be tasteful in 2025. His stories are on the sparser side in favor of the metaphorical crises he presents. The symbolic imagery shifts between intimate closeups to dream sequences for a raw cinematic experience.

James Cameron

The Explorer. Cameron is a Canadian disruptor, your average truck driver that prior to creating adventure movies had little technical experience. In an industry full of nepotism, he worked his way up and blasted onto the scene with iconic action flicks like The Terminator (1984) and Aliens (1986). Cameron made flicks he wanted to see often involving his hobby of deep sea excursions. He would continue to mark his legacy of high production value movies creating one of the greatest practical sets of all time on the Titanic (1997). Despite most of his filmography being entertaining popcorn flicks, one cannot deny the success of his box office franchises. His trilogy Avatar (2009) is his calling, pioneering state of the art CGI and 3D experiences.

Jean-Luc Godard

Le Baguette. The face of the French New Wave, Godard is considered the more radical and experimental pioneer compared to François Truffaut. While Truffaut was exploring serious social issues, Godard focused on style in Pierrot le fou (1965) through jump cuts, handheld, natural lighting and non-linear storytelling to break from traditional cinema. These would develop into a whimsical style that culminated in Breathless (À Bout de Souffle) (1960). Godard would even allow actors to break the fourth wall, symbolizing French rebelliousness, a recurring motif in French resistance and revolution. The movement was a massive departure from traditional classics and would go on to influence Hollywood thereafter. As Godard is more revolutionary, he is definitely one of the spicier leads of French cinema.

Jean-Pierre Melville

The Fedora. There were many directors I could have chosen to represent French cinema but I always find myself enamored with Jean-Pierre Melville. His film Le Samouraï (1967) was one of the most interesting films I’ve ever watched and has stuck with me. He is often known for these spy films Army of Shadows (1969) and heist films Le Cercle Rouge (1970). The presentation in his work stands out for the long cuts and cool atmosphere that allow the scene to breathe. Many other French directors simply have a whimsical wit about them that make for cult of personality but not long lasting legacy.

Joachim Trier

The Millenial. When I think of Scandinavian cinema, I think of either Thomas Vinterberg or Trier. Although I prefer the films from Vinterberg more, Trier has gained a massive reputation for his timely influential films in the 2020s such as The Worst Person in the World (2021). The Norwegian director creates subtle dramas delving deep into the intimate and personal relationships of his flawed characters, which often require reading in between the subtext. There is a realism and rawness in how he approaches character building in Sentimental Value (2025) that characterize his European sensibilities. Tier has garnered acclaim from the cinephile community for his post-modernist style that should speak to millenials that present themselves more put together than they actually are.

John Carpenter

Synthesizer Horror. John Carpenter is known for a specific type of slasher, his best work being The Thing (1982). His style revolves around Halloween theatrics mixed with anticipation rather than outright gore, like a masked villain standing menacingly in the background. Carpenter’s films tonally don’t take themselves particularly seriously especially with the emphasis on heavy synths, which have nevertheless made their influence on the horror genre. I love how much trash he talks about other films and you can also feel from watching his films, he tells it like it is.

Jordan Peele

The Comedian. Peele is an African American comedy writer turned horror filmmaker, something that only makes sense if you see horror as scary amusement. His masterpiece Get Out (2017) revolutionized the genre making art house horror accessible all while adding political commentary. Most notably, his films don’t utilize cliché moody lighting and are actually quite colorful and vibrant in Nope (2022), a contrast that is now growing in popularity. This makes for unpredictable turns but also complements his mission of correcting past horror tropes by introducing competent horror protagonists.

Lars von Trier

The Provocateur. Of all the titles to attribute, this may be the most tame. The controversial Danish director is known to be a troll, a bad person, a hater of mankind, or all three. But what no one can dispute is him being a gifted filmmaker. Utilizing German expressionism, classical music, and chapters, Trier has a stark visual style with handheld zooms to provide a raw, documentary-like experience in Breaking the Waves (1996). This fits his narratives, allowing audiences to focus on his moral experiments condemning humanity without visual distraction in Dogville (2003). His films intentionally look dirty with poor image quality to reflect the worst of humanity, with the exception of art film Melancholia (2011). His themes deal with depression, morality, suffering and range from offensive to taboo, evident from his infamous jokes on Nazism at Cannes. This is a disturbing director who is difficult to promote but is nevertheless one of the most subversively engaging.

Lee Chang-dong

The Author. Lee is a Korean author turned filmmaker revealing why his films have masterful control of literary execution. If you don’t read, then his films could feel a bit too sophisticated but if one has a mature palate then he could be one of smartest unheard of filmmakers. His masterpiece Burning (2018), inspired by a William Faulkner short story, is the film you should first start out with. If you like it, then try Poetry (2010) for one of the most sacred and emotional experiences. Lee has a style that makes you feel you are reading a book and watching a movie at the same time. He finds beauty in the most random of places by utilizing natural camera movement, framing and lighting. Naturalism and literary are two words that come to mind. The Korean Haneke.

Luca Guadagnino

Electric Love. Guadagnino is an Italian filmmaker known for his contemporary erotic style. He often forays into LGB themes, though never in an obnoxiously doctrinal way. His films are designed to be sexy and electric evidenced by the experimental tennis film Challengers (2024). But at his core, he seems to focus on relationships whether it is vacation love in Call Me By Your Name (2017) or supernatural love in Bones and All (2022). He will definitely be remembered for his more explicit LGB films, but I think these are his best so far.

Lynne Ramsay

The Trauma. Ramsay is a Scottish filmmaker blasting onto the scene with Ratcatcher (1999). She has an independent filmmaking approach, utilizing minimalism and avoiding flair so as to not distract from the serious drama she attempts to explore. Her films have a personal intimacy to them while not being overly sentimental or self-indulgent. This contrast works for the serious issues she tackles such as with the school shooter in We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) or child trafficking in You Were Never Really Here (2017). Ramsay borders on auteur filmmaking and makes art house indie films relating to trauma and is definitely one of the underrated artists I’m personally a very big fan of.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa

The Atmosphere. Although not related to Akira Kurosawa, Kiyoshi also displays a a deft gift in filmmaking. His forté lies in Japanese supernatural horror mixed with detective work. However, he has only really made 2 good films namely Cure (1997) and Pulse (2001). But they are so memorable that he deserves to be mentioned here for creating such original horror. At his best, his style is immersive, cerebral and psychologically invasive assembling a complete cinematic spectrum of sound and visuals.

Makoto Shinkai

The Wish. Shinkai is an animator that stands apart from Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki for his lavish and modern anime style involving teenagers and romantic stories. His claim to fame was Your Name (2016) though has created even more beautiful works as far old as 5 Centimeters per Second (2007) and The Garden of Words (2013). His films have gorgeous photorealistic image fidelity, but are still less charming than the bubbly hand drawn Ghibli style.

Martin McDonagh

The Playwright. McDonagh is a brilliant British filmmaker known for his wit and off-beat writing. He started with the cult favorite In Bruges (2008) and then began making thematic films like The Banshees of Inisherin (2022). What makes him stand out are his well written screenplays due to him being is a playwright. Although he still has yet to catch a break, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri (2017) was as close as he got to mass mainstream success. McDonagh is one of the most underrated directors whose work for whatever reason doesn’t seem to catch fire. But if you want some fresh wit, his voice cannot be recommended enough.

Martin Scorsese

The Perspective. Scorsese is considered an undeniable master if not for the sheer volume of films he has produced. He is known for his gangster films Goodfellas (1990) and The Departed (2006) but does diversify into other genres like religion in Silence (2016) and comedy in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). Actually many of his films have some comedic aspects to them especially his gangster films, which always have signature scenes of over the top violence as that’s what he experienced growing up on the blocks of NYC. Scorsese’s mission seems to be about retelling real stories from interesting perspectives. What illustrates his greatness is he is also able to tackle psychological themes through Taxi Driver (1976) and Shutter Island (2010), making him more than just a one trick pony. Nevertheless, his legacy is in the gangster genre.

Michael Haneke

The Abyss. Haneke is a German-Austrian filmmaker who makes films in many languages though most notably in French. He is an auteur director that explores psychological themes of social estrangement with gravitas. There is a certain intensity emanating from his style coming from a theater background. His films are mature, serious and meant to be watched with concentration. This is managed by executing with the most minimal cinematography process possible. The Piano Teacher (2001) explores sexual repression, The White Ribbon (2009) explores the brith of fascism and his masterpiece Caché (2005) explores the psyche of the French denial. He is the final boss of cinema and although I consider him one of the highest intellect filmmakers, his films are not designed to entertain nor even make you satisfied. They are intended for you to confront the dark abyss and promote discussion, all while wearing a black turtle neck.

Nicolas Winding Refn

The Quiet Kid. Refn is a Danish filmmaker known for his Pusher series and magmum opus Drive (2011). Refn has an art house approach that can go to exaggerated lengths like in The Neon Demon (2016), though it is undeniable that he does so with style. His films always have cinematic flair whether through color, lighting or music while also having a signature calmness and lurking danger. He is also deceptively attuned to framing the composition to fit the themes he portrays.

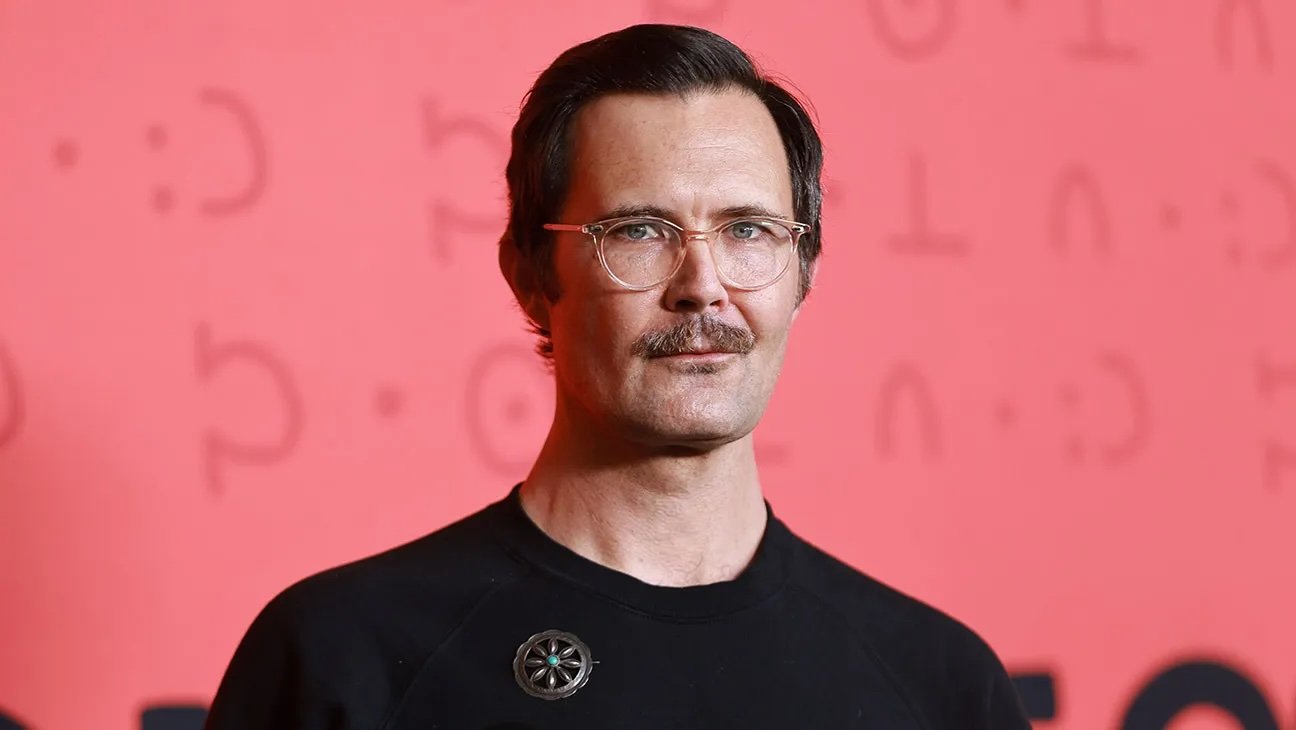

Osgood Perkins

Rock N Horror. Normally nepotism is looked down upon, but this is a special case. The son of Anthony Perkins, whom played Normal Bates, has a tragic backstory where his parents fate mirrored their horror themed work. Osgood ends up a director following in the footprints of a horrific destiny and demonstrates massive potential with films like Longlegs (2024). He’s not exactly polished in his execution with a “screw it, let’s ball” attitude providing the charm for his laid back popcorn approach. Although many of his films lack cohesion, he is one hit away from being recognized for his gifted instincts for cool horror.

Park Chan Wook

The Eccentric. Park is a Korean director known for some of the most creative transitions in cinema. Like many Korean films, he often explores revenge through his trilogy Lady Vengeance (2005) and his claim to fame Oldboy (2003). However, the eccentric director does have a quirky side as shown in I'm a Cyborg, But That's OK (2006) and makes English films with Korean sensibilities in Stoker (2013). He is likely the most stylish Korean filmmaker capable of complex camera movement and has enough personality to support his darker psychological themes in his masterpiece The Handmaiden (2016). In my opinion, he is Korea’s greatest cinematic gift.

Paul Thomas Anderson

The Arc. Anderson is an American filmmaker whom is claimed to be the competitive foil to Tarantino. Anderson focuses on writing and has a literary depth to his character building, whom are all very well developed in Magnolia (1999), Boogie Nights (1997) and The Master (2012). He is no stranger to dealing with political commentary with There Will Be Blood (2007) and his recent films. His films are relatively not as visually cinematic or showy compared to other directors. Instead, his characters bring his stories to life and feel substantial due to well written scripts and fleshed out themes in Phantom Thread (2017). Anderson does not chase clout nor box office success and the running joke is his films never make money.

Pedro Almodóvar

The Spice. The Spanish auteur is known for his seductive art films about sexuality, love, desire, often from the female point of view in Volver (2006). His use of color is vibrant with with rich, decadent reds, which pair well with this theatrical melodrama in Talk to Her (2002). There is an intense emotional complexity to his characters in The Skin I Live In (2011), or perhaps it is in the nature of Spanish being such a romantic language. Nevertheless, passion and style oozes out from all of his films. Although he is primarily recognized for sexy films unafraid of nudity, he also has a mature side diving into tragedy and comedy. Almodóvar always presents a strong sense of fashion whether it is in his films or real life.

Quentin Tarantino

The VHS Clerk. The greatest director to make a popcorn flick, he is the equivalent of a Michelin star McDonald’s chef. Tarantino is a savant film nerd that has encyclopedic memory of every film he’s watched, allowing him to revive actor’s careers while discovering the next big star. He’s outspoken, unapologetic and that’s why we love him. His style involves vivid characters, unpredictable scripts and cathartic violence. Sometimes his presentation can feel cartoonish from the dramatic zooms or bigger than life performances of Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction (1994). Tarantino seems heavily influenced by westerns and Japanese cinema and will copy and paste scenes into his own, often times better than the original. He regularly parodies obscure film references for fan service i.e. Django Unchained (2012). In keeping with cathartic satisfaction, many of his films revise history in Inglorious Basterds (2009) and Once Upon a Time… In Hollywood (2019). His writing aims to have highs of ecstasy followed by sudden drops of emotional despair. Tarantino is the epitome of fan service and giving what audiences want is what makes his movies awesome.

Richard Linklater

The Time Capsule. Linklater is a unique filmmaker who makes films involving the passage of time. His film Boyhood (2014) follows the same boy actually growing up over real world years. In his romance epic trilogy Before Sunrise / Sunset / Midnight (1995-2013), he follows the same actors over nearly 2 decades long utilizing a one shot one take style for maximum realism. When he’s not making groundbreaking films, he often explores suburban settings and school life in Dazed and Confused (1993). Linklater is a filmmaker known not just for his realistically grounded films, but for creating films that have a reality in themselves.

Ridley Scott

The Paycheck. Scott is an English filmmaker known for his masterpieces Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982). He is notable for pioneering blockbuster scale and production value through miniatures and has a keen sense of mass appeal coming from commercial work. As a result, he often seems more motivated by the bag than creating true cinema these days, though one could make the argument that he has always been this way. Scott has made many successful hits including Gladiator (2000) and Black Hawk Down (2001), but his films became more uninspired over time, churning out generic popcorn flicks like All the Money in the World (2017) and House of Gucci (2021). His last great film was The Last Duel (2021). Still, he creates entertaining films despite them feeling like they were made on an assembly line.

Rob Reiner

The Natural. The late actor has a streak of legendary films culminating with Stand By Me (1986). He is known for creating some of the most beloved classics across many genres like family fantasy The Princess Bride (1987) and the greatest music mockumentary This is Spinal Tap (1984). Reiner has a sense of humor and humility to his films despite being an activist and is beloved for his grounded approach, which makes his films nostalgic by today’s standards.

Robert Eggers

The Film Student. Eggers is exactly the kind of director you’d think that came fresh out of NYU film school. The art house director appeals to his roots in theater and is a pioneer in contemporary A24 films. He has carved a niche in exploring folklore, mysticism and mythology and prioritizes conveying thematic elements rather than story. Being research based, he is historically accurate but concentrates on metaphors leaving inconsistencies in logical framework. He began with exhibitionist horrors The Witch (2015) and The Lighthouse (2019) leading to his prized vocation Nosferatu (2024). Eggers has a Shakespearean quality to his voice, which can feel pretentious and frustrating as if watching a dissertation. He refuses to film anything with modern cars, a pretty good synopsis of his visual style. Regardless of whether you think he takes his films too seriously, the edge lord is a proper contemporary auteur.

Roman Polanski

The Loner. Putting his personal dishonor aside, Polanski is a Polish-French filmmaker known for his masterpieces The Pianist (2002) and Chinatown (1974) showcasing his signature theme of isolation. He has a timeless greatness underscoring his films similar to Francis Ford Coppola’s. His films are serious and give nods to classic noir through his signature cold atmosphere and detailed camera work seen in Rosemary's Baby (1968).

Roy Andersson

The Absurdist. Relatively obscure, the contemporary Swedish director is perhaps known more for his commercials than films, which are all equally visually striking. His work stands out for their deliberately staged scenes and sickly muted color palettes. As a result, his desaturated style has a surreal gloominess reminiscent of moody paintings most exemplified in A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (2014). One can immediately recognize an Andersson film, which always have a complex attention to framing to present his unconventional absurdism, his masterpiece being Songs From the Second Floor (2000). Unfortunately he doesn’t make many films - A shame because he may have one of the spicier styles in the Hall of Spice. His films like You, the Living (2007) are somewhat similar to a black comedy version of Wes Anderson.

Safdies

The Concrete Jungle. Benny and Josh Safdie are at heart independent filmmakers from NYC. Their films often feature New York City, Coney Island and the frantic pace of the concrete jungle in Good Time (2017). Their rise to stardom came with the acclaimed film Uncut Gems (2019). Although the obsession genre was really first pioneered by Aronofsky, the Safdie brothers dialed the chaos to 11 creating the most stressful films of all time and potentially a new genre of struggle. They have an explosive style of editing that is borderline OCD, enabling stressful experiences that feel like a controlled demolition. This is enabled by handheld camera work and getting up close and personal on 16mm film for its grainy texture, often using foreground to create an eavesdropping perspective. However, they ended up parting ways into their own projects and it is very interesting to see their differences in direction.

Sam Mendes

Lightning in the Bottle. Not many directors can say their first film won Best Picture. Mendes is one of the only ones to do it for creating American Beauty (1999). Mendes can create beautiful films even about war with his one shot film 1917 (2019). His style can be summarized as attempting to capture lightning in the bottle, which he repeatedly does but is hit or miss. I greatly enjoyed Empire of Light (2022) but most audiences did not find the Oscar grabber favorable. Mendes combines sensitivity with repressed themes to make films that are designed to be universally touching.

Satoshi Kon

The Rabbit Hole. The second greatest animator of all time, Satoshi Kon has a more standard visual hand drawn style that is more nostalgic to retro classic anime. However his films delve much deeper into psychology with Paprika (2006) and Perfect Blue (2001) compared to Ghibli animation. His other films like Millennium Actress (2001) and Tokyo Godfathers (2003) also have a journey of descent, often hallucinatory.

Sergio Leone

The Western. Leone is an Italian filmmaker and the greatest westerns director of all time. Leone has a masterful understanding of framing and proportions where nearly every frame from his films could be hung on a wall. He is best known for his western masterpieces The Good, The Bad And The Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), but does go outside of his genre with gangster epics like Once Upon a Time in America (1984). His films are ambitious, thematic but he himself has always stated that westerns are not a serious genre. As a result, his films always have a sense of humor and style to them.

Sidney Lumet

The Speaker. No fluff and all substance, the one to have style in having no style. Lumet is one of the greatest filmmakers during the mid era of cinema, known for 12 Angry Men (1957), Network (1976) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975). His work often highlights the working class and social injustices with satirical wit. Compared to the poetic flourishes from his peers, Lumet focused on realism and efficient dialogue.

Spike Lee

Black Power. Whereas Steve McQueen resembles MLK, Spike Lee resembles Malcom X. His mission seems to raise black communities and voice their frustrations with society through iconic social commentary Do the Right Thing (1989). Lee is very outspoken and has a colorful personality mirroring his vibrant cinematography, which contrasts with an underlying anger. He is extremely political and promotes more aggressive social change with a blend of humor. There is a quirkiness to his style in both film and fashion crossing politics with art, most notably the double dolly shot and dutch angles.

Stanley Kubrick

The Psychologist. Kubrick was originally a photographer before becoming one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. As a result, Kubrick is highly attuned to framing his scenes like a portrait, where every scene is a painting in Barry Lyndon (1975). He often employs symmetrical compositions in The Shining (1980) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) and has left his legacy of creating the greatest sci-fi epic of all time 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Kubrick is known for meticulous obsession, even to the point of abusing his cast to elicit results. He is also known to be political and creates true anti-war films such as Dr. Strangelove (1964). His films get better over time especially once he begins delving into more psychological topics with Full Metal Jacket (1987) and his final enigmatic hurrah Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Kubrick is the GOAT not because of any one film, it is his consistency in creating masterpiece after masterpiece with the perfect balance of cinematic elements.

Steve McQueen

The Empath. McQueen, not to be confused with the actor, is an African-American filmmaker most well known for 12 Years a Slave (2013). Unlike other one-trick directors like Coogler, McQueen empowers Black history and modern struggles with maturity. He can diversify into other genres with Shame (2011) and doesn’t only care about race themed victim politics. His films have personal touches of compassion even for those that we wouldn’t normally think of.

Steven Soderbergh

The Web. Soderbergh is an American filmmaker pioneering the advent of modern cinema. His style of storytelling uses interlinking story arcs in Traffic (2000), Contagion (2011) and most notably Ocean’s Eleven (2001). Although his work prioritizes story, he is not afraid to utilize technology in Presence (2024) where he utilizes mirrorless cameras in inventive ways.

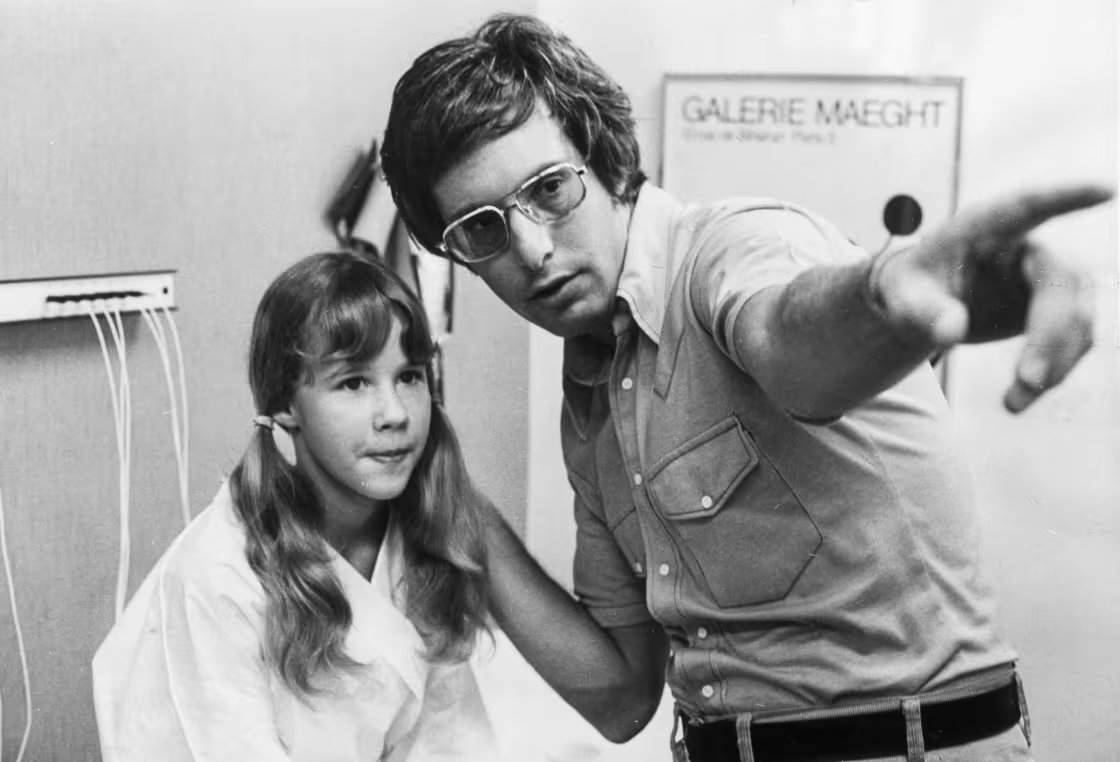

Steven Spielberg

The Blockbuster. Spielberg is one of the greatest filmmakers known for dominating the 70s-90s with blockbuster hit after hit. Although he is often associated with sci-fi stories like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), there are simply too many culturally significant films to name them all. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) was the globetrotting adventure of a generation, Jaws (1975) made society irrationally afraid of beaches, Saving Private Ryan (1998) recreated the Storming of Normandy so realistically it was played in schools. Although his films aim for commercial success and popcorn enjoyment, he is also to be taken seriously with emotional masterpieces like Schindler’s List (1993). Speilberg is known for his immersive camera movement and precise blocking, aesthetically framing the scene to generate subjective perspectives. His films have tremendous mainstream influence while having clear nods to classic cinema.

Terrence Malick

The Therapist. The director that makes films from his journal entries. I often tease Malick, but he’s a great filmmaker - him being so mawkish just puts such an easy target on his back. His poetic mood pieces are highly evocative and intended to be Christian philosophical, but sometimes can feel out of place with random nature reels in The Tree of Life (2011) and The Thin Red Line (1998). But at his best, Malick is capable of uncovering true beauty in the mundane with visually charged frames, like finding surprises underneath the rocks and leaves, a dollar in your pocket or a potato wedge in your French fries. Days of Heaven (1978) and Badlands (1973) are breathtakingly beautiful films known for their tactile and sensory experiences. There is a sense of spontaneity in his work through handheld participatory camera work and editing. Nevertheless they are all beautiful with natural lighting. His sensitive style is characterized by sentimental narration designed to nourish the soul in his most gorgeous piece A Hidden Life (2019). His weakness is he is too honest and sometimes needs to be reeled in, and that’s where storytelling was supposed to come in.

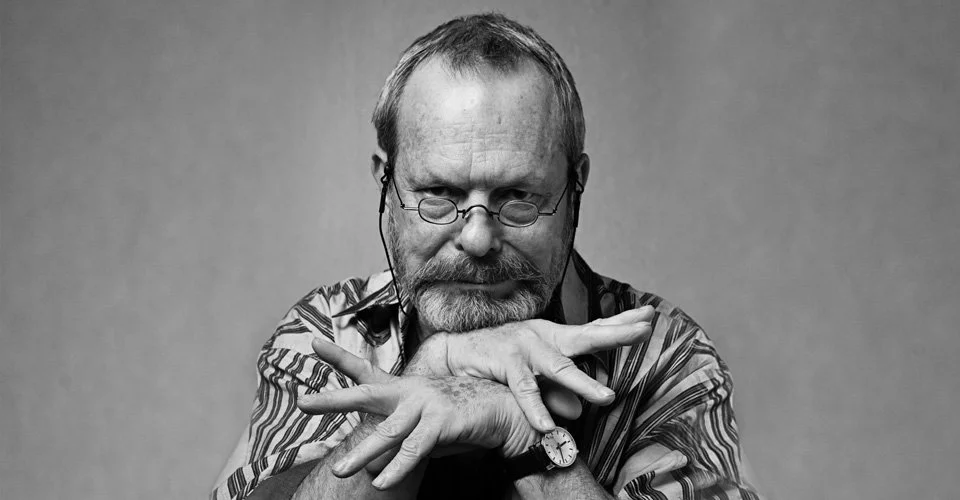

Terry Gilliam

The Fever Dream. Most known for his humor in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Gilliam has a distinct visual style with extravagant sets and costumes that create labyrinth-like scenes. He never aims for realistic props, which lend to a quirkier nature despite thematically rich puzzles in 12 Monkeys (1995). His films often incorporate chaotic and layered fantasies such as in Brazil (1985), his most ambitious work. Satirical, whimsical, imaginative, Gilliam is a unique amalgam of traits that one would not generally pair with his thematic depth. His cinematic techniques often include wide angle shots and tall top down vantage points to evoke the isolated insanity of his character’s dilemmas.

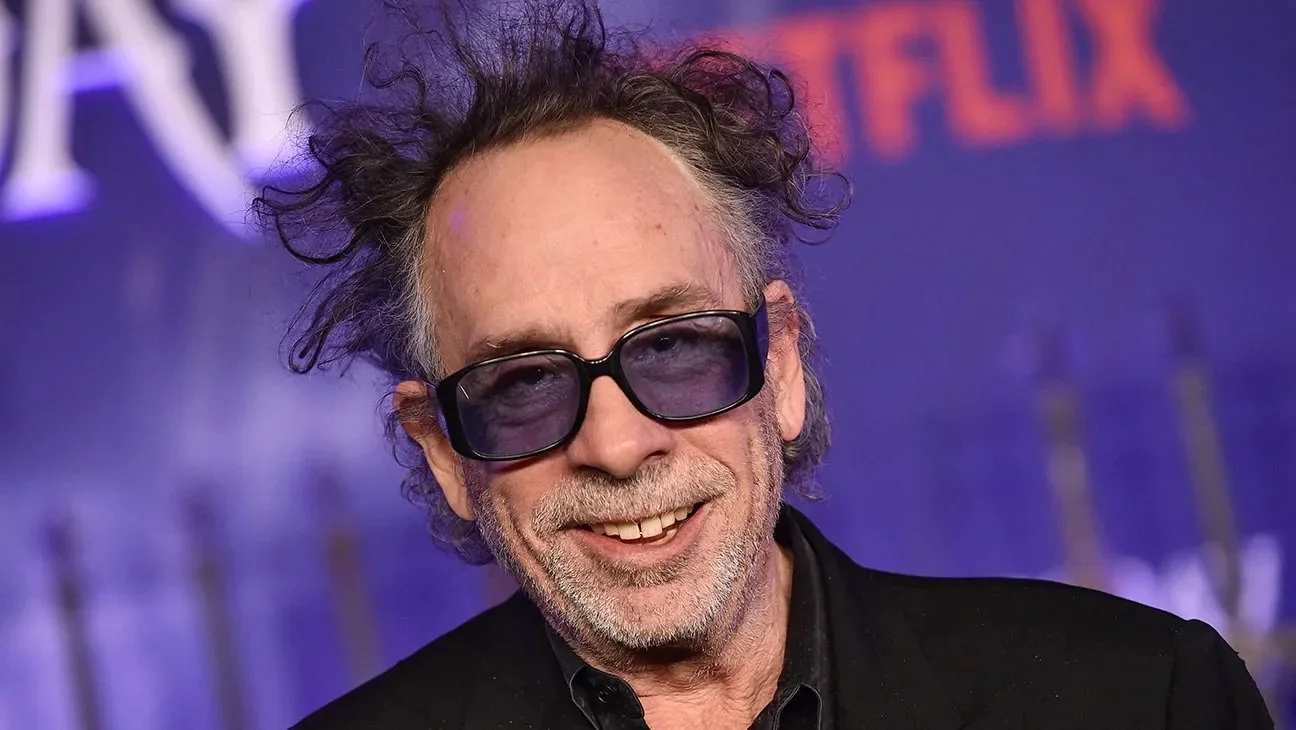

Tim Burton

The Goth Kid. Burton is known for his gothic style blended with a peculiar quirkiness. His core are family focused fairy tales Edward Scissorhands (1990) and Big Fish (2003). His characters often become delightfully cartoonish caricatures in Sleepy Hollow (1999) due to unserious dialogue. The levity seems more suited toward television than modern cinema, prioritizing set and costume designs to produce his signature theatrical flair.

Tsai Ming-liang

Teenage Angst. Tsai is in my opinion the most electric voice in the second new wave of Taiwanese cinema. Although technically born in Malaysia, Tsai captures the lower class struggles of Taiwanese youth with visceral mood pieces like Rebels of the Neon God (1992). His underground films are highly evocative appealing to hipsters and rebellious cinephiles through atmosphere and sexual exploration exemplified in Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003). Sometimes Asian films are too reserved for western audiences, but Tsai films are the only ones from Taiwanese cinema that are unique enough to reach western audiences in my view. He is the closest to Wong Kar Wai, utilizing neon lights of Taiwan to similar effect, but distinguishes himself with a sense of gloominess.

Wachowskis

The Matrix. The transgender duo is known for their revolutionary martial focused films The Matrix (1999) and assistance on V For Vendetta (2005). The reason their films feel so incredibly visceral is because they were conceived from a stunt perspective, enabling inventive action sequences like the iconic bullet time. This would go on to influence the John Wick series, providing proof of concept that action films can start from the stunt coordinator phase. Although they have not created anything meaningful since, one iconic trilogy is enough to put their names in the Hall of Spice.

Wes Anderson

The Hipster Theater Kid. Preferring colorful jackets over red plaid, Wes Anderson is a unique individual who attempts to bring storybooks and theatre to cinema. With humble beginnings, his films were initially story focused in Rushmore (1998). Anderson’s style is characterized by symmetrical framing, 90 degrees pans, title cards and quirky dialogue. He would go on to implement these traits in stop motion film Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) and others. His magnum opuses are Moonrise Kingdom (2012) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), which at his best captures childhood innocence from an adult perspective. But his films have increasingly become self-indulgent globetrotting art projects like The French Dispatch (2021), which feel overly-pretentious and offer no restraint or substance to the viewing experience.

William Friedkin

The Exposition. A hidden gem of the 70s, Friedkin has a particular visceral style, which complements his action thrillers such as The French Connection (1971) and Sorcerer (1977). His visuals can be characterized by his dirty and realistic images using any available natural light. This complements car chases and running sequences, which are emphasized by his handheld style. Story-wise he often implements a 2 part narrative structure with half of the film being exposition and character introduction with the second half filled with excitement or horror in The Exorcist (1973). This allows his characters to be more than cannon fodder and build stakes for the audience to invest in his characters. He often has an international approach framing the perspective of his film from foreign countries and languages.

Wim Wenders

The Observer. Wenders is a German filmmaker who focuses on memory and alienation. His films have a contemplative mood in Perfect Days (2023) and Wings of Desire (1987). Known for his photography, his films have a similarly silent stillness covering sweeping landscapes as seen in his masterpiece Paris, Texas (1984). However, the melancholic pacing can be interpreted as slow by many, though Hou Hsien-hsiao probably takes the crown for that.

Wong Kar Wai

The Nostalgia. Wong is the most notable Hong Kong director to western audiences, or to be more specific, western hipsters. His nostalgic style is accomplished by evocative ultra wides, slow motion and choppy shutter speeds amidst the neon and grungy city lights of Hong Kong. Many will cite his romance epic In The Mood For Love (2000) to be a masterpiece, which I personally didn’t get. But if you want to get the full Wong Kar Wai experience, it has to be Fallen Angels (1995) and then Chungking Express (1994), which are nostalgic, episodic snapshots capturing fleeting moments. Speaking to our rebellious natures, his movies now embody the modern cinephile.

Woody Allen

The Hopeless Romantic. Ignoring his personal life, Allen is a smart and witty person injecting his flawed personality into his films, whether welcome or not. His greatest film is Annie Hall (1977) and he often creates narration based love letters particularly to NYC. When he’s not self-absorbed, he is capable of creating truly mesmerizing stories whether it is a love letter to literature with Midnight in Paris (2011), a love letter to polyamory with Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), or a love letter to infidelity with Match Point (2005). It’s quite clear that he is romance focused and once you see his life choices perhaps it is more on the perverted side. But if you can divorce his life from his work, there is a pretty unique voice emanating from that taboo mind.

Yorgos Lanthimos

The Alien. Lanthimos is an alien from another planet, which happens to be called Greece. He is known for his independent and absurdist approach, crafting absurd stories to heightened realities giving food for thought. He began with Dogtooth (2009), the most pure form of Lanthimos’ freaky mind. Out of all synonyms for the word strange, bizarre is the most apt to describe his style, juxtaposed by his naturalistic lighting. He is sort of a Salvador Dali or Picasso figure when it comes to filmmaking, which is weird when you see he is a pretty reasonable guy in interviews. All of his films investigate an absurdity in our society whether it is marriage in The Lobster (2015) or loyalty in Kinds of Kindness (2024). His most mainstream film is The Favourite (2018), which marks the beginning of weird ultra wides. Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) is a unique horror with long zooms. Poor Things (2023) is a generational masterpiece, a culmination of his filmmaking journey between the dance montages, imagery overload and absurdist social commentary. The most exciting working filmmaker capable of rewriting reality.

Zach Cregger

The Twist. Cregger is a supposedly apolitical director who crafts inventive suburban horror twists in Barbarian (2022) and Weapons (2025). As he is quite young, he is growing into someone to look out for due to his distinctly unpredictable direction. I mean look at him, he doesn’t even have a full beard - everyone knows you can’t be a respectable filmmaker until you have one. The way he pilots a contemporary thriller is genuinely refreshing. With his current trajectory, he is on track to dethrone Shyamalan.

Zack Snyder

The Grit. Snyder is known for the dark DC Universe, but has always held a notably gritty approach as can be seen in Watchmen (2009). When he’s not doing superhero films, he demonstrates that he’s also able to make equally bleak films in other genres such as Dawn of the Dead (2004) and 300. He knows his audience and doesn’t pretend he’s above creating simple yet awesome popcorn entertainment.

Zhang Yimou

The Prestige. Zhang is mainland China’s greatest director, known for epic Wuxia spectacles Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004). Despite Chinese censorship, Yimou is able to tell profound operatic stories in nuanced ways with Raise The Red Lantern (1991). Even with the handicap, he’s able to create spectacular cinema even for the 2008 Olympic Opening Ceremony, proving that nothing can hold him back from creating art. Like most mainland Chinese cinema, his style is flowery, ornate and overly poetic, an unavoidable result of 5000 years of cultural history.

Honorable Mentions

Brady Corbet

The Roots. The up and coming American filmmaker is known for The Brutalist (2024), a honest take on capitalism. From his interviews, he does not seem political, but rather genuinely attempting to uncover answers to the societal questions he poses. His search for the origin seems genuine but it may not always seem that way from his films. In any case, he has a blend of modern visuals with classic presentation rooted in real drama while pushing technological mediums. He is known to make long films with bigger than life vistas while forming intimate connections with his characters. Someone to look out for, Corbet seemingly has a lot more to say after graduating from acting.

Greta Gerwig

The Feminist. Started out acting, Gerwig is an American director with a unique voice that caters to female audiences. There is a light sense of personality and disarming quirkiness that can be felt in Lady Bird (2017), drawing from her real and oddly specific experiences. These would lead into the colorful phenomenon that is Barbie (2023). Despite her feminist focus, her execution of themes are not as shallow as many would claim them to be as she has a more nuanced attitude on the modern do-everything girl boss.

Sean Baker

The Listener. Baker is an NYU alumni who creates indie films with any tools necessary, even an iPhone on Tangerine (2015). This makes sense when you realize the guy is still broke despite winning best picture for Anora (2024). He doesn’t seem to be interested in abandoning his indie style, featuring stories about marginalized groups like immigrants and sex workers. His films draw inspiration from real people and feel authentic as a result.

M. Night Shyamalan

Popcorn Suspense. A budget Hitchcock, Shyamalan employs supernatural twists placed at the very end of the film for maximum shock and awe, making for fun popcorn flicks and memorable taglines like in The Sixth Sense (1999). His movies are simple but are still guilty pleasures for the masses. He made a very promising superhero series starting with Unbreakable (2000) but seems to be running out of steam these days with uninspired slop.

Mel Gibson

The Christian. Mel Gibson is an American filmmaker attempting to make heartfelt stories. He doesn’t really have a lot of psychological depth making his movies comparable to Clint Eastwood popcorn flicks, but generally does a distinct enough job to stand out. As a Christian, he often implements some religious elements to his films such as with Braveheart (1995) and Hacksaw Ridge (2016), but never out of nowhere. He doesn’t have a political agenda, rather he chooses films with topics he’s interested in, which is why religion is so prevalent. Malick also shares this title.

Alex Garland

The Writer. British filmmaker Garland started out indie and gritty, writing 28 Days Later (2002) and would take a turn into the art house genre. This was solidified by his success in Ex Machina (2014), then slowly teetering off the deep end. He would go on to create flop after flop landing himself in movie jail with Annihilation (2018) in trying to reach the same highs. This is because at his core, Garland is a writer, not a director, forced into the profession after the Dredd (2012) debacle. As a result, he often tries to incorporate literary themes and metaphors to varying effect in Men (2022) and Civil War (2024). His execution wavers significantly and has not created anything as meaningful as his past works. For better or worse, his films are a mess yet still unlike anything you’ve seen before. He will still often write for other modern films making him relevant.

Edward Berger

The Camera Lover. Berger is a young Swiss-Austrian director known for creating visual leading stories such as All Quiet on the Western Front (2022) and Conclave (2024). For this reason, all his films are cinematography focused and look beautiful, but he seems more interested in making pretty pictures than stories. He is really more of a DP than a filmmaker, regularly implementing camera techniques like focus racks, shallow depth of field and the most modern equipment in a contemporary style. He will often present frames that have nothing to do with the story for the sake of a highlight reel. Berger has much to prove to stay on this list.

Edgar Wright

The Kinetic. Wright is known for high concept creative films like Scott Pilgrim Vs The World (2010) and Baby Driver (2017). Considered an action filmmaker, his innovation is stylish enough to distinguish himself from other generic action directors by incorporating British wit. His style is accomplished through the use of colorful effects, whether they are practical or through high concept editing. His signature technique is the long tracking shot with a steadicam seen in Hot Fuzz (2007).

Michael Mann

The Heat. Mann is known for his riveting crime films Heat (1995) and Collateral (2004). Back when 10 police cars speeding down the highway was peak cinema, he was really in his element. His style of action filmmaking is straightforward, direct and he is at his best when he implements cat and mouse devices. However, he seems to struggle to adapt to modern filmmaking sensibilities because “cool” is very different in 2025.

Charlie Chaplin

Thomas Vinterberg

Jim Jarmusch

Robert Bresson

Agnès Varda

Orson Welles

John Ford

Milos Forman

Robert Zemeckis

Ron Howard

Peter Jackson

George Lucas

Michael Bay

Emerald Fennell

When losing a bike loses everything.